2 million Congolese refugees fled their homes in 2017, bringing the total internally displaced to 4.5 million. The displacement is accelerating, with over 600,000 fleeing their homes in the last two months.

As President Joseph Kabila enters the seventh year of his five-year term, he is struggling to maintain authority as the Congolese provinces are increasingly spiraling out of control. 10 of the 26 provinces are currently in armed conflict, and with a central government incapable of response, experts project that the situation is only going to get worse.

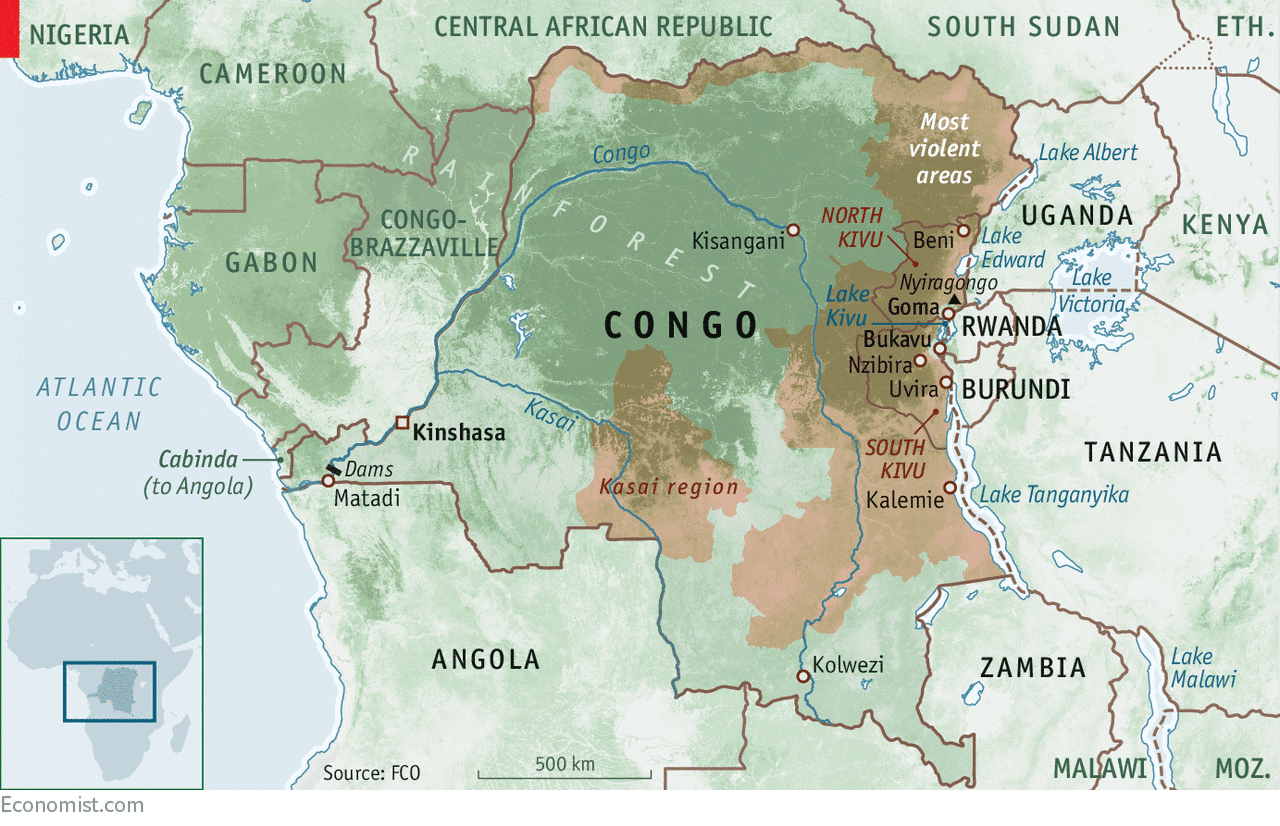

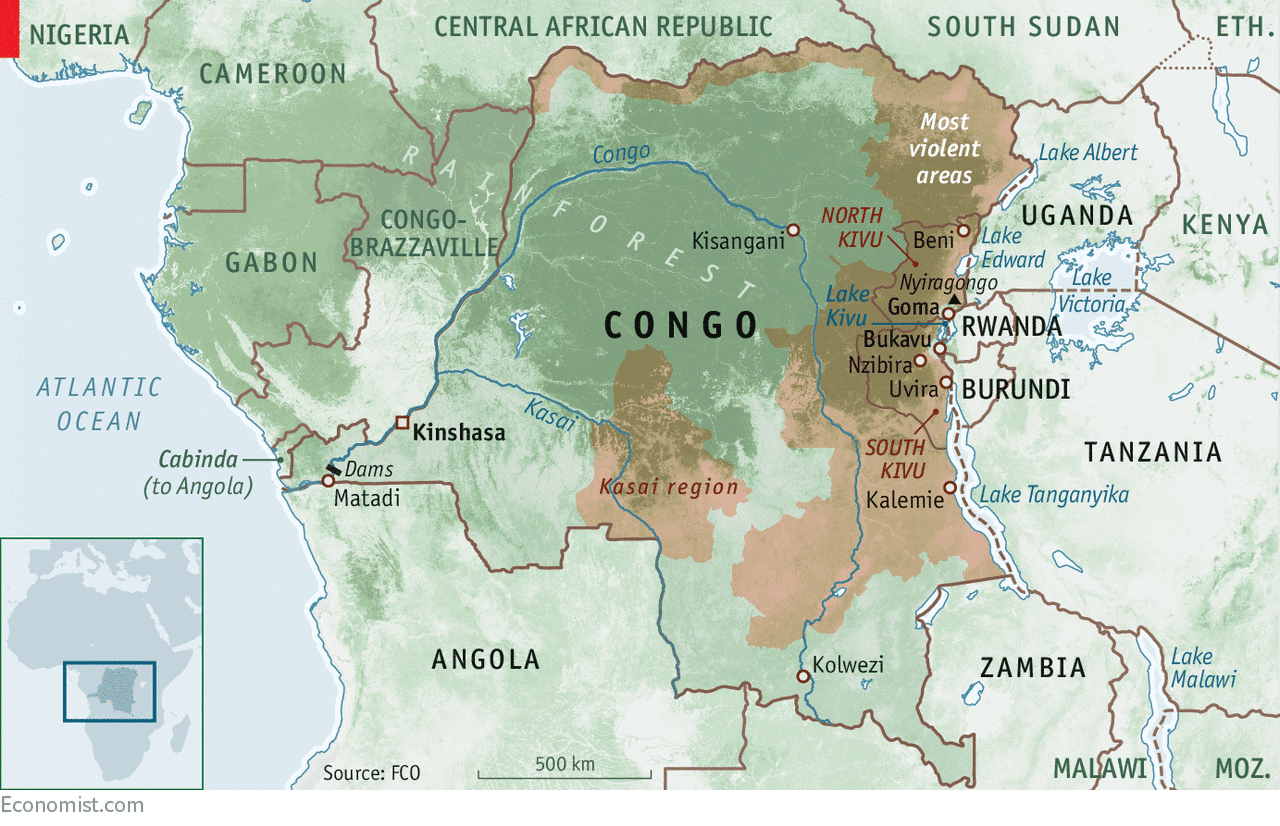

In September, a group called Mai Mai Yakutumba, led by the Babembe rebel William Amuri Yakutumba, attacked the lakeside city of Uvira in South Kivu. Faced with the challenge, the Congolese army fled and left Pakistani UN peacekeepers to repel the attack. In the North Kivu city of Beni, another attack left a UN expert decapitated. However, these attacks in the provinces of North and South Kivu are not necessarily unusual; the region has been almost perpetually destabilized since the refugee crisis following the 1994 Rwandan genocide.

What is happening is a proliferation of violence to new parts of the country; Kasai in the center of the country, Tanganyika to the South of the two Kivu provinces, the boarder region of Beni with Uganda, and the entire stretch of the northern border.

The conflict in Kasai escalated in August 2016, when the central government killed a prominent local chief. Relations between Kasai and the central government were already tense, as the region is an opposition stronghold. Since the death of the chief, what was a confrontation between a chief, an individual clan, and the central government, has spiraled into ethnic violence.

– Entrenched conflicts between ethnic groups

– Fierce clashes between Congolese armed forces + militias

– New armed groups threaten to wreak havocA humanitarian disaster of extraordinary proportions is about to hit the southeastern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo pic.twitter.com/jHqzKuUwHl

— UN Refugee Agency (@Refugees) February 20, 2018

Meanwhile, the violence in Tanganyika is partially owed to the spill over of Mai Mai rebels from South Kivu, but there is also growing violence between the Twa and Luba ethnic groups. Although these groups have fought before, the UN backed a peace deal between the two in October 2015 which was held for some time. The recent clashes started when the Luba were accused of levying a tax on caterpillars in October 2016, a local delicacy and one of the primary products of the Twa.

Although Muslim militants from Uganda have been in Beni for years, they have proven increasingly effective. An attack carried out in December was the bloodiest the U.N. has experienced since attacks in Somalia in 1993. This is an area where the central government is moving aggressively to counter the militants, but to mixed results; the counter-offensive last month against the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), an Islamist insurgency originally based in Uganda, sent 370,000 Congolese fleeing from their homes.

The violence along the northern border is largely owed to the destabilization of the Central African Republic and South Sudan.

While the country is spiraling out of control, the central government is struggling with a political crisis. Since December 2016, President Kabila has faced off with protestors lead by Étienne Tshisekedi, a revered political figure who cut his teeth in the struggle against the former dictator in the early 1990s. Kabila acquiesced, and agreed to elections to be held by the end of 2017. However, in February 2017 Tshisekedi died, and the deal for elections broke down. Elections are coming up on December 23rd, and in spite of Kabila’s unpopularity, the lack of leadership in the opposition will hurt their prospects.

The Congo’s conflict history parallels the country’s economy-defining events. Misery driven by resource extraction has been fairly consistent for the better part of six centuries. First, the European colonies in the Americas relied heavily on the Congo River Basin for slave exports to produce tobacco and sugar. Then the Congo was a leading source of ivory. Then the Belgian Congo waged an all out war in the country to force the production of rubber, and now the country’s metals have new-found value in our electronics. Every one of these booms in violence was to satisfy a demand for consumer goods.

[Title image: Armed conflicts accelerate as the central government loses control in the Congo. Photo: Guy Oliver/IRIN]

Recommended reading: “Humble in the jungle: Meeting the gorillas of war-torn Congo” – The Telegraph, Feb. 22, 2018

LIMA CHARLIE NEWS, with Diego Lynch

Lima Charlie provides global news, insight & analysis by military veterans and service members Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it:

2 million Congolese refugees fled their homes in 2017, bringing the total internally displaced to 4.5 million. The displacement is accelerating, with over 600,000 fleeing their homes in the last two months.

As President Joseph Kabila enters the seventh year of his five-year term, he is struggling to maintain authority as the Congolese provinces are increasingly spiraling out of control. 10 of the 26 provinces are currently in armed conflict, and with a central government incapable of response, experts project that the situation is only going to get worse.

In September, a group called Mai Mai Yakutumba, led by the Babembe rebel William Amuri Yakutumba, attacked the lakeside city of Uvira in South Kivu. Faced with the challenge, the Congolese army fled and left Pakistani UN peacekeepers to repel the attack. In the North Kivu city of Beni, another attack left a UN expert decapitated. However, these attacks in the provinces of North and South Kivu are not necessarily unusual; the region has been almost perpetually destabilized since the refugee crisis following the 1994 Rwandan genocide.

What is happening is a proliferation of violence to new parts of the country; Kasai in the center of the country, Tanganyika to the South of the two Kivu provinces, the boarder region of Beni with Uganda, and the entire stretch of the northern border.

The conflict in Kasai escalated in August 2016, when the central government killed a prominent local chief. Relations between Kasai and the central government were already tense, as the region is an opposition stronghold. Since the death of the chief, what was a confrontation between a chief, an individual clan, and the central government, has spiraled into ethnic violence.

– Entrenched conflicts between ethnic groups

– Fierce clashes between Congolese armed forces + militias

– New armed groups threaten to wreak havocA humanitarian disaster of extraordinary proportions is about to hit the southeastern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo pic.twitter.com/jHqzKuUwHl

— UN Refugee Agency (@Refugees) February 20, 2018

Meanwhile, the violence in Tanganyika is partially owed to the spill over of Mai Mai rebels from South Kivu, but there is also growing violence between the Twa and Luba ethnic groups. Although these groups have fought before, the UN backed a peace deal between the two in October 2015 which was held for some time. The recent clashes started when the Luba were accused of levying a tax on caterpillars in October 2016, a local delicacy and one of the primary products of the Twa.

Although Muslim militants from Uganda have been in Beni for years, they have proven increasingly effective. An attack carried out in December was the bloodiest the U.N. has experienced since attacks in Somalia in 1993. This is an area where the central government is moving aggressively to counter the militants, but to mixed results; the counter-offensive last month against the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), an Islamist insurgency originally based in Uganda, sent 370,000 Congolese fleeing from their homes.

The violence along the northern border is largely owed to the destabilization of the Central African Republic and South Sudan.

While the country is spiraling out of control, the central government is struggling with a political crisis. Since December 2016, President Kabila has faced off with protestors lead by Étienne Tshisekedi, a revered political figure who cut his teeth in the struggle against the former dictator in the early 1990s. Kabila acquiesced, and agreed to elections to be held by the end of 2017. However, in February 2017 Tshisekedi died, and the deal for elections broke down. Elections are coming up on December 23rd, and in spite of Kabila’s unpopularity, the lack of leadership in the opposition will hurt their prospects.

The Congo’s conflict history parallels the country’s economy-defining events. Misery driven by resource extraction has been fairly consistent for the better part of six centuries. First, the European colonies in the Americas relied heavily on the Congo River Basin for slave exports to produce tobacco and sugar. Then the Congo was a leading source of ivory. Then the Belgian Congo waged an all out war in the country to force the production of rubber, and now the country’s metals have new-found value in our electronics. Every one of these booms in violence was to satisfy a demand for consumer goods.

[Title image: Armed conflicts accelerate as the central government loses control in the Congo. Photo: Guy Oliver/IRIN]

Recommended reading: “Humble in the jungle: Meeting the gorillas of war-torn Congo” – The Telegraph, Feb. 22, 2018

LIMA CHARLIE NEWS, with Diego Lynch

Lima Charlie provides global news, insight & analysis by military veterans and service members Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it: