When Mohammad Azams lifeless body was found on the side of the road in the Bidar district nine months ago, authorities were left with few answers. It was another installment in a string of social media-induced killings, which have become a serious problem in India.

The 27-year-old and his friends were beaten to death by a 2,000-deep angry mob after false rumors circulated on WhatsApp falsely accusing the innocent travelers of being child-kidnappers. Both tech companies and governments have taken measures to limit the spread of viral lynch mobs, but the problem is growing, with authorities grasping for tools to combat the threat.

WhatsApp, the most popular messenger app in the world, deals with many of the same disinformation-related concerns as its parent company Facebook, but faces these issues on a much larger scale. The persistent problem ramps up around election time with heightened rumors and politically-motivated content. (RELATED: How Fake News Texts About Child Abductors, Organ Harvesters Are Triggering Mob Violence In India)

With more than 815 million people registered to vote, the upcoming general election in India is projected to be the biggest democratic election in world history. The magnitude of the event adds pressure to an already dire situation.

Indian activists take part in a protest against mob lynchings in India, in Ahmedabad on July 23, 2018. – More than 20 people have been killed in similar incidents in the past two months, leaving both the Indian authorities and Facebook-owned WhatsApp scrambling to find a solution in its biggest market. (Photo by Sam Panthaky / AFP / Getty Images)

The child kidnapping rumors that went viral through the messaging service have spurred mobs resulting in the lynching of 33 people since January 2017, according to Poynter. The Facebook subsidiary took to the press Feb. 6 to make it clear they intend to avoid a similar disaster in Indias upcoming election, set to begin April 11.

“We have engaged with political parties to explain our firm view that WhatsApp is not a broadcast platform and is not a place to send messages at scale,” spokesman Carl Woog told the media in New Delhi, according to CNN. “We will be banning accounts that engage in [suspicious] behavior.” The company took steps to limit the number of forwards allowed on the platform in January, in an effort to check the problem.

Nevertheless the app is highly susceptible to spam messaging because of the layout of the platform. The ability to create mass groups and forward content from group to group with the click of a button, without fact checks or labels, has led to the viral spread of false content that is nearly impossible to track back to its source.

Whereas investigations into the role of such campaigns in United States elections have focused largely on Russian-perpetrated interference, Indias problems come from within; political parties are among the biggest culprits of disinformation dissemination.

Party workers run scripts that analyze what users in political groups are saying, and then exploit those conversations through mass-distributed messages. The staffers then use public group invite links to circumvent WhatsApps spam detection software and overload their party groups, according to ET Prime.

One story that exploded onto the national scene through the app last year contained the now-infamous rumors regarding child kidnappings. Messages alleged that 500 people dressed as vagrants would be roaming the streets of one of Indias central regions looking for people to kill for their body parts, and that 400 child traffickers would be in town for a child-abducting campaign.

This photo illustration shows an Indian newspaper vendor reading a newspaper with a full back page advertisement from WhatsApp intended to counter fake information, in New Delhi on July 10, 2018. – Facebook owned messaging service WhatsApp on July 10 published full-page advertisements in Indian dailies in a bid to counter fake information that has sparked mob lynching attacks across the country. (Photo by Prakash Singh / AFP / Getty Images)

Playing off fears of abductions, the false reports prompted a series of brutal beatings and killings across the country, including the lynching of a 26-year-old construction worker. It only later surfaced that the rumored perpetrators were uninvolved, and the story was completely fake.

In order to combat such behavior, WhatsApp is now implementing AI technology to identify and delete spam accounts and label forwarded messages as unoriginal content. The new tools have assisted in the removal of over 6 million accounts globally throughout the last three months, according to WhatsApp spokesman Carl Woog. (RELATED: Co-Founder Of WhatsApp To Leave Facebook After Alleged Disagreements)

The platform has also met with the Elections Commission of India, and warned political parties that they will be blocked if they commit any infringement of the apps regulations, including sending mass unsolicited messages.

While it may seem conceivable that Indian citizens could just disregard messages spread on the platform, the nature of communications in the South Asian nation makes that notion a near impossibility.

Self-censorship has skyrocketed in light of Hindu nationalists campaigns to eliminate “anti-national” discourse from mainstream media, and journalists have been killed for reporting information unfavorable to the governing administration, according to Reporters Without Borders.

Mobile social media services then become pivotal to the unfiltered communication of information; the only problem is that the information is not verified, and in many cases, is not verifiable by the average citizen. With many Indian citizens poorly educated and on the internet for the first time, it is an environment ripe for convincing disinformation.

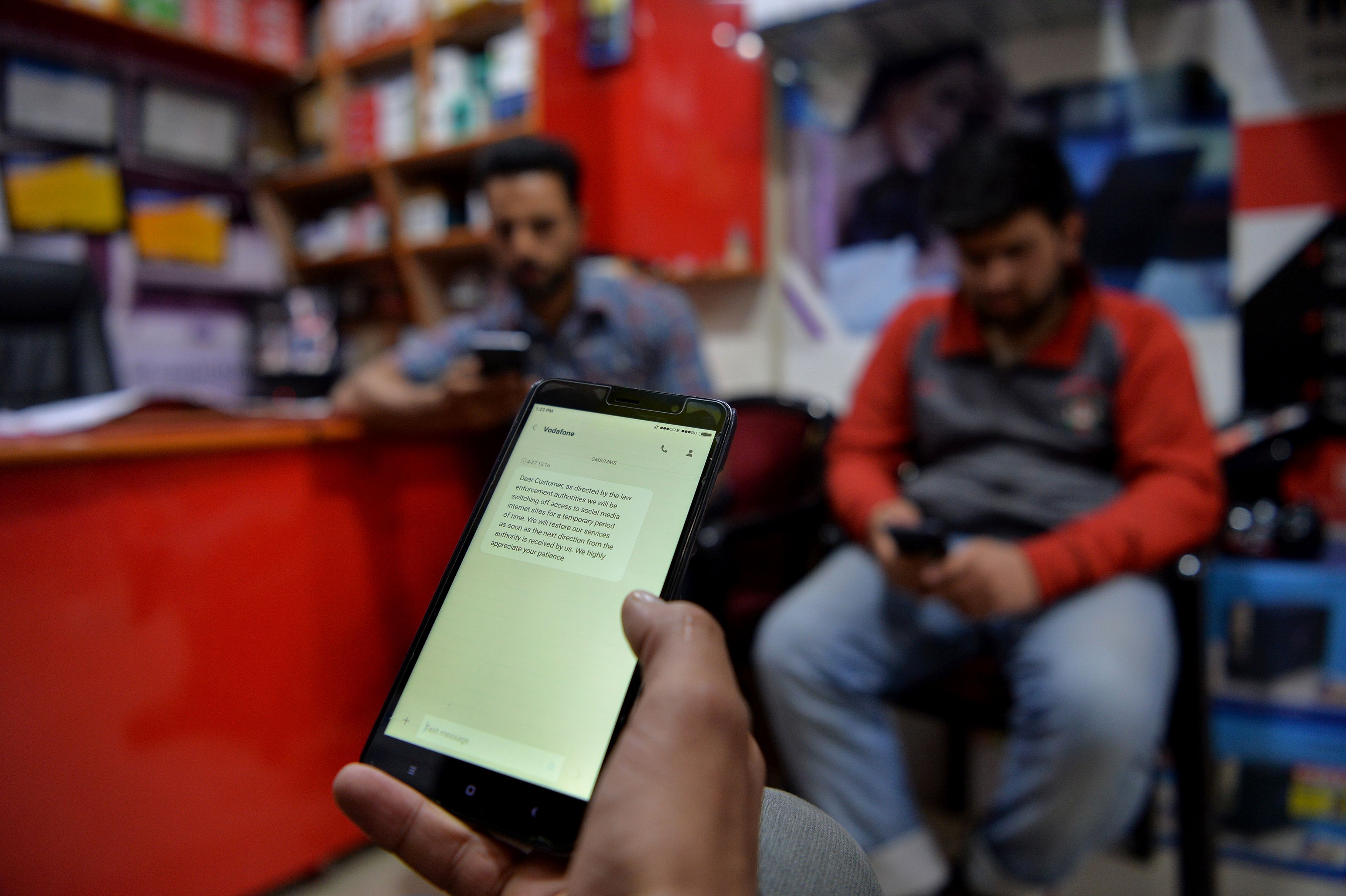

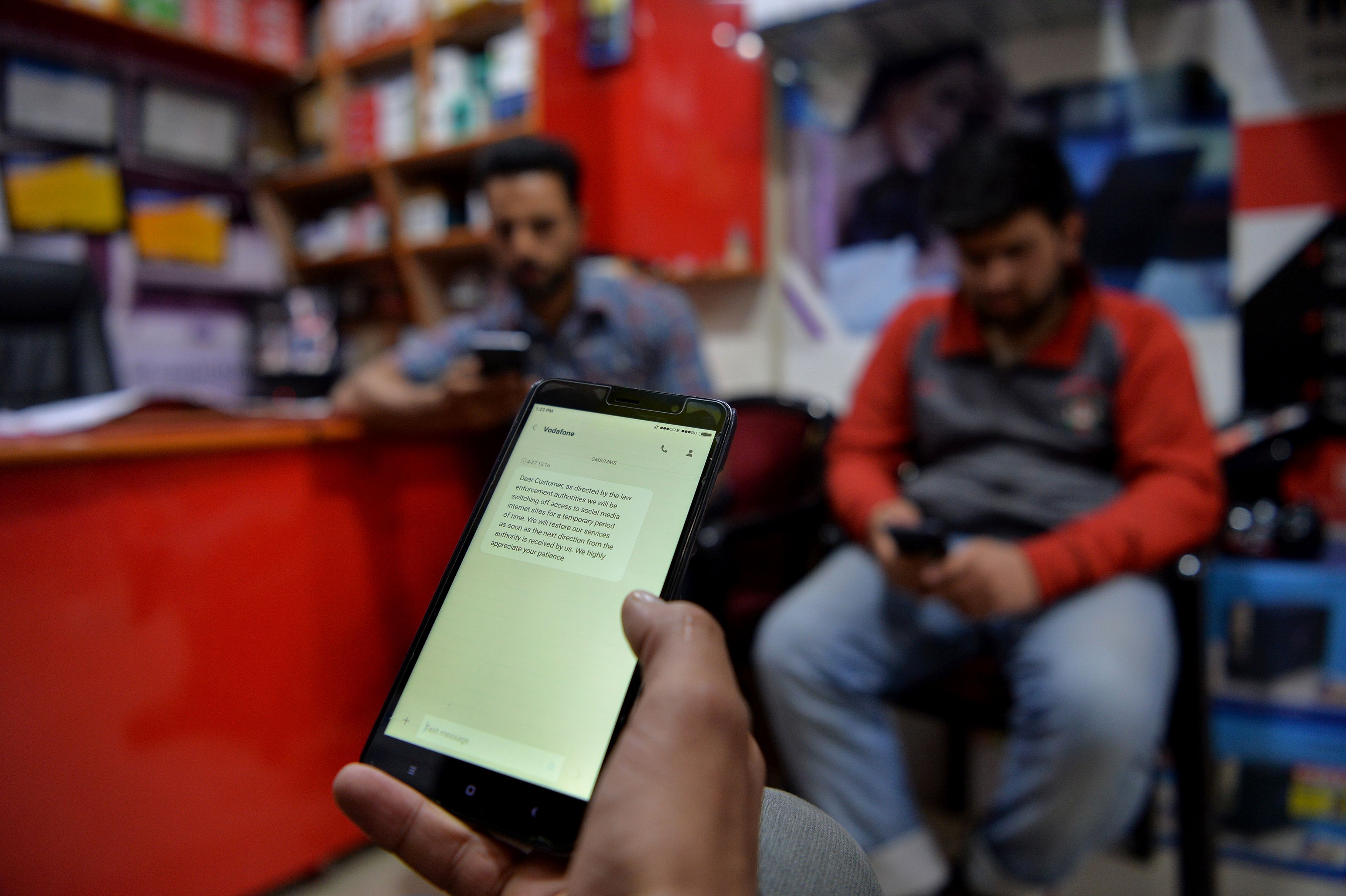

An Indian Kashmiri man browses the internet on his mobile phone in a shop in Srinagar on April 27, 2017. Authorities in Indian-administered Kashmir on April 26 ordered internet service providers to block popular social media services including Facebook, Twitter and WhatsApp after an upsurge in violence in the region. (Photo by Tauseef Mustafa/AFP/Getty Images)

WhatsApp made headlines in Feb. 2018 when the application reached 200 million users in India, and Economic Times Prime reported that the figure could be anywhere from 250 to 400 million users now.

While Americans spend an average of 18 percent of their daily mobile internet time on the trio of major Facebook-owned social media apps Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram, Indians spend a whopping 38 percent of their daily mobile internet time on such services, according to The Times of India. And while fake news has arguably been used to impact American politics, fake news in India can be deadly.

Some Indian officials, such as Vishwas Pandhare, the superintendent of police that rose to the top post in the wake of last years WhatsApp-related killings, believe the app is a matter of life and death.

“People in India can live without oxygen,” he told Wired. “But without WhatsApp, they will die.”

While Instagram and Facebook may not face the same threat levels in the upcoming campaign cycle as WhatsApp, they are still a big part of the Indian social media landscape, and are preparing for the election in a similar manner.

“Instagram and Facebook teams work together to identify and disrupt information operations on our platforms,” an Instagram representative told The Daily Caller in a statement.

“Information operations are when sophisticated threat actors run coordinated efforts to mislead and manipulate the public. As part of these efforts, we are in regular contact with law enforcement, outside experts and other companies around the world.”

Some experts are skeptical as to whether these measures will effectively address the problem, or whether the problem can be fixed by digital stopgaps alone.

“These are like Band-Aids,” said Dr. Kalyani Chadha, Associate Professor at the University of Maryland and co-founder of the Journalism Interactive Conference. “In India, the biggest proRead More – Source

When Mohammad Azams lifeless body was found on the side of the road in the Bidar district nine months ago, authorities were left with few answers. It was another installment in a string of social media-induced killings, which have become a serious problem in India.

The 27-year-old and his friends were beaten to death by a 2,000-deep angry mob after false rumors circulated on WhatsApp falsely accusing the innocent travelers of being child-kidnappers. Both tech companies and governments have taken measures to limit the spread of viral lynch mobs, but the problem is growing, with authorities grasping for tools to combat the threat.

WhatsApp, the most popular messenger app in the world, deals with many of the same disinformation-related concerns as its parent company Facebook, but faces these issues on a much larger scale. The persistent problem ramps up around election time with heightened rumors and politically-motivated content. (RELATED: How Fake News Texts About Child Abductors, Organ Harvesters Are Triggering Mob Violence In India)

With more than 815 million people registered to vote, the upcoming general election in India is projected to be the biggest democratic election in world history. The magnitude of the event adds pressure to an already dire situation.

Indian activists take part in a protest against mob lynchings in India, in Ahmedabad on July 23, 2018. – More than 20 people have been killed in similar incidents in the past two months, leaving both the Indian authorities and Facebook-owned WhatsApp scrambling to find a solution in its biggest market. (Photo by Sam Panthaky / AFP / Getty Images)

The child kidnapping rumors that went viral through the messaging service have spurred mobs resulting in the lynching of 33 people since January 2017, according to Poynter. The Facebook subsidiary took to the press Feb. 6 to make it clear they intend to avoid a similar disaster in Indias upcoming election, set to begin April 11.

“We have engaged with political parties to explain our firm view that WhatsApp is not a broadcast platform and is not a place to send messages at scale,” spokesman Carl Woog told the media in New Delhi, according to CNN. “We will be banning accounts that engage in [suspicious] behavior.” The company took steps to limit the number of forwards allowed on the platform in January, in an effort to check the problem.

Nevertheless the app is highly susceptible to spam messaging because of the layout of the platform. The ability to create mass groups and forward content from group to group with the click of a button, without fact checks or labels, has led to the viral spread of false content that is nearly impossible to track back to its source.

Whereas investigations into the role of such campaigns in United States elections have focused largely on Russian-perpetrated interference, Indias problems come from within; political parties are among the biggest culprits of disinformation dissemination.

Party workers run scripts that analyze what users in political groups are saying, and then exploit those conversations through mass-distributed messages. The staffers then use public group invite links to circumvent WhatsApps spam detection software and overload their party groups, according to ET Prime.

One story that exploded onto the national scene through the app last year contained the now-infamous rumors regarding child kidnappings. Messages alleged that 500 people dressed as vagrants would be roaming the streets of one of Indias central regions looking for people to kill for their body parts, and that 400 child traffickers would be in town for a child-abducting campaign.

This photo illustration shows an Indian newspaper vendor reading a newspaper with a full back page advertisement from WhatsApp intended to counter fake information, in New Delhi on July 10, 2018. – Facebook owned messaging service WhatsApp on July 10 published full-page advertisements in Indian dailies in a bid to counter fake information that has sparked mob lynching attacks across the country. (Photo by Prakash Singh / AFP / Getty Images)

Playing off fears of abductions, the false reports prompted a series of brutal beatings and killings across the country, including the lynching of a 26-year-old construction worker. It only later surfaced that the rumored perpetrators were uninvolved, and the story was completely fake.

In order to combat such behavior, WhatsApp is now implementing AI technology to identify and delete spam accounts and label forwarded messages as unoriginal content. The new tools have assisted in the removal of over 6 million accounts globally throughout the last three months, according to WhatsApp spokesman Carl Woog. (RELATED: Co-Founder Of WhatsApp To Leave Facebook After Alleged Disagreements)

The platform has also met with the Elections Commission of India, and warned political parties that they will be blocked if they commit any infringement of the apps regulations, including sending mass unsolicited messages.

While it may seem conceivable that Indian citizens could just disregard messages spread on the platform, the nature of communications in the South Asian nation makes that notion a near impossibility.

Self-censorship has skyrocketed in light of Hindu nationalists campaigns to eliminate “anti-national” discourse from mainstream media, and journalists have been killed for reporting information unfavorable to the governing administration, according to Reporters Without Borders.

Mobile social media services then become pivotal to the unfiltered communication of information; the only problem is that the information is not verified, and in many cases, is not verifiable by the average citizen. With many Indian citizens poorly educated and on the internet for the first time, it is an environment ripe for convincing disinformation.

An Indian Kashmiri man browses the internet on his mobile phone in a shop in Srinagar on April 27, 2017. Authorities in Indian-administered Kashmir on April 26 ordered internet service providers to block popular social media services including Facebook, Twitter and WhatsApp after an upsurge in violence in the region. (Photo by Tauseef Mustafa/AFP/Getty Images)

WhatsApp made headlines in Feb. 2018 when the application reached 200 million users in India, and Economic Times Prime reported that the figure could be anywhere from 250 to 400 million users now.

While Americans spend an average of 18 percent of their daily mobile internet time on the trio of major Facebook-owned social media apps Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram, Indians spend a whopping 38 percent of their daily mobile internet time on such services, according to The Times of India. And while fake news has arguably been used to impact American politics, fake news in India can be deadly.

Some Indian officials, such as Vishwas Pandhare, the superintendent of police that rose to the top post in the wake of last years WhatsApp-related killings, believe the app is a matter of life and death.

“People in India can live without oxygen,” he told Wired. “But without WhatsApp, they will die.”

While Instagram and Facebook may not face the same threat levels in the upcoming campaign cycle as WhatsApp, they are still a big part of the Indian social media landscape, and are preparing for the election in a similar manner.

“Instagram and Facebook teams work together to identify and disrupt information operations on our platforms,” an Instagram representative told The Daily Caller in a statement.

“Information operations are when sophisticated threat actors run coordinated efforts to mislead and manipulate the public. As part of these efforts, we are in regular contact with law enforcement, outside experts and other companies around the world.”

Some experts are skeptical as to whether these measures will effectively address the problem, or whether the problem can be fixed by digital stopgaps alone.

“These are like Band-Aids,” said Dr. Kalyani Chadha, Associate Professor at the University of Maryland and co-founder of the Journalism Interactive Conference. “In India, the biggest proRead More – Source